Learning to Bend

- Anna Koziarski

- Nov 25, 2022

- 7 min read

Hello, and thank you so much for clicking on this, my first blog entry for Engage! It is also Thanksgiving, so my warmest greetings to all who celebrate it as the holiday season begins. It’s been very exciting hearing all of the positive feedback we have received in recent months, and I can’t tell you how much it means to me. This entire endeavour has been a labour of love and my greatest gratitude must go to Michael Bradley for having the vision and the gumption to make this happen.

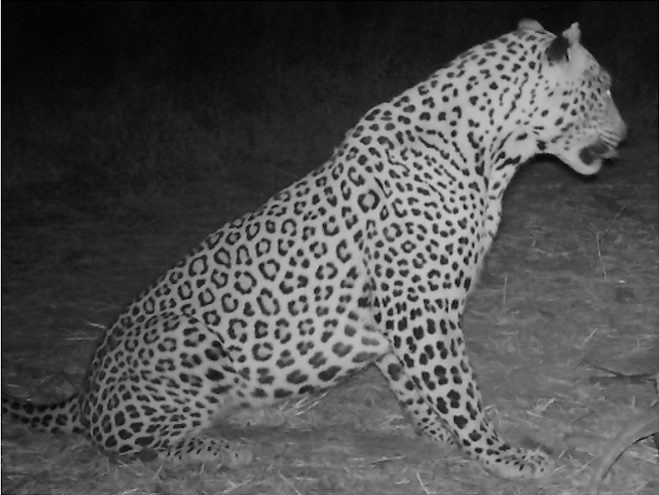

I remember how Mike and I spent many evenings in Mapungubwe talking about what kind of future we could forge in Africa as wildlife professionals. (Check out Mike’s previous blog post, for more of his account of our time in Mapungubwe). We both knew we wanted to create something where we could learn, grow, and share the beauty of Africa with others. We would sit there in our backyard, our faces lit only by fire light, as we listened to the distant (and often not-so-distant) calls of leopards and hyenas. In the trees just beyond, “fairies” twinkled in the branches. The fairies were actually curious bushbabies, tiny nocturnal primates whose incongruously giant eyes would shimmer and shine in the night. At the time, our dream of building a research conservation company seemed as close, and yet as ethereal, as the fairies. It’s funny to look back on that time now as that dream is being realized.

It is even funnier to remember that when we arrived in Mapungubwe, Mike and I were as adversarial as cats and dogs.

But before diving into that, I’d like to take a step back and talk a bit more about my background. Like many people who take up the wildlife profession, I was first inspired by watching the biologists and educators who hosted TV wildlife documentaries. I was fortunate enough to travel all over the world during my school and college years, but the African savannah and bushveld were always my favorite.

In 2018, I arranged to travel to the Limpopo region of South Africa for my master thesis work. I developed a study on wild lion field monitoring as part of a larger project for the South African wildlife department. Little is known about the lion population in the Mapungubwe/Tuli region, and the objective was simple: Determine the best method of monitoring the population in the expansive bushveld. Much easier said than done, but more on that later. The project was to be wholly independent, which was a big step for me. I had done a couple of research expeditions before, but always as part of a collaborative group, and with an itinerary arranged for me ahead of time. This time, as there was barely any research presence in Mapungubwe, it was up to me to figure out all of the logistics: How to finance the trip? Where do I rent an appropriate vehicle from? How many and what kind of supplies do I need? How will I get there? The knowledge that I was about to wander into a remote part of Africa with little to no backup was sobering.

Truth be told, I was petrified. I felt like I had a lot to prove both to myself, and to others. I was relieved when I was able to find a research assistant who could provide support during the project: none other than Engage Conservation Founder-to-be, Michael Bradley. Although we were little alike, we managed to find common ground on our interest in skull morphologies and of course our love of Africa, and I was truly happy to have him on board. But I also felt the pressure to appear competent, and to show that I was capable of being an independent wildlife researcher.

Unfortunately, personal and medical reasons meant that I had to push my planned arrival date to Limpopo back by a week–not a great start. Then the second day after I belatedly arrived, I twisted my ankle stepping off a five-inch step because I wasn’t looking where I was going–a humbling maneuver if ever there was one, and one that, in hindsight, had tremendous metaphorical potential. I wasn’t badly injured and I could still walk, but it easily could have been worse. The bush was trying to tell me something: slow down, think…because This Is Africa. It is beautiful, but it can also be unforgiving.

The weeks that followed were a baptism by fire. Driving a 4x4 at a >50° lateral and linear angle, cooking over a campfire, learning the intricacies of wildlife tracking, just to name a few skills. I had the extraordinary privilege of meeting and learning from the incredible staff and managers of the reserve. These were lessons that no student could ever hope to learn about from a book, and I will always be grateful for the traditional and professional knowledge that they shared with me.

Most of the time, however, Mike and I were left to explore the seemingly endless reserve on our own terms. Mapungubwe had no maps, and we had to rely on our knowledge of the routes in order to find our way. There were deep gorges, sand pits, secluded watering holes, and impenetrable bushvelds, all of which we discovered as they came to us. The feeling of being lost is at once exhilarating and terrifying. Things can go very badly if you are caught out in the wilderness. But you will only discover something for the first time once. The feeling of being lost is non-renewable, and one that I know Mike and I both reveled in.

As incredible as it was to explore and live in the bush, I was acutely aware that I was there for a job. I had given myself just 2 months to collect the field data I would need for my thesis, which included several replications of several different wildlife monitoring procedures, most of which involved camera arrays. The original plan was to find the lions within the first week and follow them from there, working out the most reliable method of predicting their movements and numbers. But the first week passed and though we occasionally would find lion spoor, we never actually caught a glimpse of the elusive lions. With every report of lion signs at any of the various corners of the property, Mike and I would race over there with our cameras to try to catch them on film before they moved on. Each time it was to no avail. Two weeks passed, then three. I was getting more and more nervous. Afterall, my entire thesis rode on finding these lions, and it was feeling more and more like I had bitten off more than I could chew.

In the face of potential failure, a natural human reaction is denial. To compensate for my nervousness, I affected to appear as confident as possible. I was often unreasonably stubborn as I attempted to do everything by the book, worried about how my increasingly messy data would impact my final paper. After all, I had read all the books, I had worked with this species in this environment before. I should know everything, right? It was a classic case of Dunning-Kruger, and I regret to say that this negatively affected my working relationship with Mike. It was hard to let go of my pride, and to accept criticism objectively. I was so concerned about pretending that I knew what I was doing, that I was sabotaging myself by denying any opportunity to adapt.

The bush will test you. The physical dangers are not to be taken lightly, but there is also a harmony to be found. Nature is at once beautifully simple and inconceivably complex. Through much academic and personal reflection, I began to adapt my study design. In spite of the setbacks, I was accumulating a wealth of data on the other species that inhabited the reserve. Through spot recognition we identified and followed individual leopards and hyenas across the reserve, beginning to gain an understanding of their territories and movements. We even captured several interesting species interactions on camera that went against the academic consensus for behaviours. My thesis was evolving into something different than what I had set out, but that was okay. Through all the tribulations, Mike and I developed a profound respect for one another. During expeditions such as this, you are sometimes exposed to the worst side of people. But you also develop an irreplicable bond through the extraordinary, shared experience. I was, and still am, incredibly grateful to have Mike by my side.

With just two weeks left in the data collection, we determined via spoor that the lion pride was in the vicinity of a nearly dried watering hole. (I must here acknowledge that without the incredible tracking skills of the reserve manager we would never have gotten this far). We set our cameras around the area, knowing that our chances of getting them on camera were better than ever. But we had been disappointed many times before.

The next morning, we collected the SD cards, and Mike looked at the photographs in the passenger seat while I drove back to our campground.

“Oh, you’re going to be a happy woman,” he said to me with a smile.

“Lions?!”

“Lions.”

The truck could barely contain our excitement. We finally had them! Just a few blurry black-and-grey images of a sub-adult lion slinking through the dried-up basin in the dead of night, followed by a series of overexposed shots as he put his nose right up to the camera, as if to say "Hey, you found me!". The images were hardly National Geographic calibre, but I felt like we had just captured the Photograph of the Year.

Mike and I spent many hours over the closing weeks sitting in our vehicle as the pride lounged around us. It was almost like now that they had been caught on film, they were content to reveal themselves fully, and we both had plenty of opportunities to get much better photographs of the fugacious felines. Nevertheless, the first images we captured will always be top tier for me. We closed out our time in Mapungubwe thoroughly thrilled with the experience and full of optimism for the future. We both knew this was only just the beginning.

If you have read all the way to the end, I would like to extend my deepest thanks, and I look forward to remaining in touch through this blog, and even meeting some of you in the future. Until then, peace and love.

-Anna

Comments